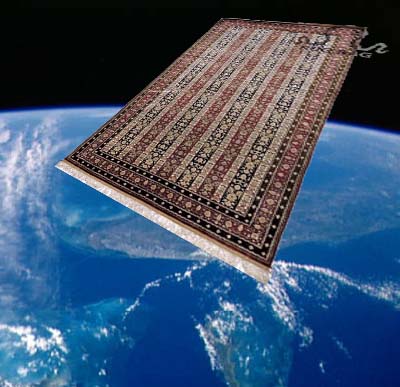

Flying Carpet

Slow as ice forming in the bay, the streets around Petoskey give up their double lining of parked cars by the end of the fall color season. Arctic winds off Lake Michigan slam doors shut, and scatter dead leaves across the brick streets. As cemetery-gray clouds pile over the water, “closed for the season” signs appear in store windows. Sooner or later, cars track new snow, and one day the mountainous spray over the channel light abruptly stops and ice brings more quiet--human quiet, then nature’s quiet. The town and bay finally stand silenced, two geometries blocked in by jagged ice fields until the Spring thaw.

In this quiet place, local news becomes important. The town paper reports the first hunter to fall out of his tree stand and the first ice fisherman to go through the ice. A boon for the economy, people cheer the first day of ski season. Around town old friends meet for lunch, and hang their coats on familiar hooks. Resized for winter, everyone slows their pace, and settles in. Those lucky enough to share their life with someone they love move closer to each other in bed. Compared to Cairo, Rozeta would find this setting distant as a remote planet, but she would also notice familiar signs of squalor and poverty.

At age thirty-one, Rozetta had never traveled beyond Egypt; she had never flown in an airplane; her exposure to televisions and computers limited to the classroom or library. Now thanks to the assistance of her benefactor who contacted an overseas recruitment firm on her behalf, she embarked for America to begin her residency in general surgery, one step away from becoming a cardiac surgeon. As she stepped onto the plane, she sent a silent prayer of lovingkindness to her benefactor:

May you be happy.

May you be peaceful.

After recovering from the excitement of the takeoff, she slept. When her eyes opened, she was over the Atlantic. Amazed she had dozed so long, she felt like she had either done something wrong, or failed to do something. Her feet felt pleasantly warm. Dressed in slacks and stockings, she had slept sideways in her window seat with her long legs and feet draped over the middle seat. As she slowly opened her eyes, she was mortified. Her feet had slipped under the rump of a handsome young man sitting in the aisle seat. She quickly closed her eyes again, and slowly drew her feet away, then turned to sit upright. Keeping her head straight forward, she slanted her eyes sideways. The young man kept reading a book, and gave no signs of disturbance. He did appear to have just the slightest hint of amusement on his face.

Rozeta wanted to use the bathroom, but could not imagine climbing over this stranger whose space she had so rudely violated. Her feet were now cold. She reached into her bag, and pulled out a sweater, slippers, and a blank notebook. She began writing busily to deflect any further contact with her seat mate. These were the first lines of her American journal:

“I am writing this on my flying carpet to America. My writing is better than my speaking. Soon I will develop perfect English as lovely as my Arabic. The two letter “Z”’s in my new name, “Zizi,” will represent the old me and the new me. Shaped like a zigzag, the “Z” letters represent the zigzag journey that is my life. I am Arab and Christian. I am a North African and will be Arab American. I can hurt and be hurt by people. I can heal and be healed. As an Egyptian, I will let go of some things, and hold on to others. I will be the same, but not the same. I am worried, but I know my family up in Heaven watches over me. They smile at me, and I smile back. I thank God I am alive, but so sorry to be without my family. From my airplane window, I sigh for the beauty outside me and inside me. I am so embarrassed about where I placed my feet!”

As the plane lowered to final descent in Detroit, Rozeta looked down upon a dismal cityscape with abandoned factories and warehouses surrounded by vacant parking lots, train stations without trains, dingy houses and schools. Her first glance at America reminded her of the garbage city of her childhood. “This cannot be America,” she thought, “America cannot be like Egypt. I want everything to be clean and pretty and safe.” The young man watched her look out the window, and observed the sad expression on her face.

“Detroit is waiting for better days--almost dragged herself off the map, but she’ll drag herself back....” The first words she heard from an American expressed an American value uncommon in Egypt: optimism.

She faced the young man and announced, “My name is Zizi.” With this simple reply, she introduced her new American name. They engaged in some chatter, and Zizi was pleased.

After clearing immigration and customs, she stepped into the Detroit Metro Airport. She looked around her for signs of America. Everyone seemed to be alone, talking into headsets while pacing up and down, left and right, tapping on laptops and cell phones. They were connected to all kinds of contraptions, but not connected to each other. She walked in and out of one-way conversations, as she searched for her next gate. The building looked as sterile as a hospital, and just as uncomfortable. The black and chrome lounge seats appeared too cold to touch. The smells of fried food filled the long terminal complex. The only animation came from children who looked like they were in charge--running around like demons, shouting at their parents, throwing food wrappers at each other, whining and crying. People were slurping straws from large plastic containers like a cartoon movie she had once seen. At one point, she heard the comforting sound of Arabic music playing through someone’s head phones.

Zizi boarded a small plane for Pellston, Michigan. Airborne, she looked out on a half-lit landscape thick with snow. She shivered. From the plane window, she saw a vast Sahara of ice and snow, uncluttered, covered over, as pristine as the first day of earth. The plane shook in the wind. When she observed ice shanties dotting the inland lakes, she thought they were houses, about the size of her cardboard shack in the Cairo dump.

For the first time, Zizi thought deeply about healing...healing herself. Could this cold new place possibly be a healing place for the miseries and agitated gloom of her childhood, a place she could live peacefully? Could there be a ground of compassion and love under all that snow? Had she suffered too long to soften her heart? Would she move to safety beyond her daily fight for survival? She hoped the pearl stars whirling above her would spin a healing web for her. As evening faded into night, the flickering ground lights became sparse as the plane flew northwest. She turned the prayer for her benefactor to a prayer for herself:

May I be peaceful.

May I be happy.

Rozeta walked down the air stairs, across the tarmac, and into the terminal filled with life-size mounts of large animals. She imagined bearish creatures lurking outside the terminal, ready to haul her into the woods. After she claimed her bag, she asked a security officer where she might connect to the train station. When she saw his puzzled face, she thought the last train had left for the night.

“Excuse me, please, when did the last train leave for Petoskey?” she said.

“About fifty years ago,” he replied.

He kindly helped her call a taxi. She walked out into the northern landscape with hesitating steps. When she arrived in her hotel room, a letter from the hospital outlined her orientation program, and other information about her general surgery residency. On her first day, she would receive an ID badge, parking permits, computer access, and an introduction to the organization and hospital layout. One big problem. Rozeta had no car, no driver’s license, and had never driven a car. Her only automobile-related possession--the silver and turquoise key chain from her benefactor.

Over the next two weeks, Zizi spent after hours looking for an apartment. She needed a place within walking distance of the hospital. Through an ad in the paper, she found a loft apartment in downtown Petoskey. Built in 1900, the building stood on Mitchell Street in the heart of the downtown area where about seventy-five other people rented on the second floors of old downtown buildings. Zizi could walk down to the Bear River, cross a bridge and walk into the hospital within fifteen minutes. Within a few weeks, she began driving lessons with an older gentleman named “Tall Bob.” She couldn’t wait to complete the program, get a license, and take her driver’s test. Her benefactor’s checks stopped after she graduated from medical school, so she set aside as much as she could to save for a car.

“Dr. Zahra” immersed herself in learning how to be effective in her work environment. She memorized the first and last names of patients, doctors, administrators, and nurses each day after work. She met everyone on the support staff--the clergy, social workers, physical therapists, cafeteria workers, and volunteers in the gift shop. She accepted advice from the senior staff willingly, and listened to her co-workers on the surgical team. Zizi treated everyone with respect, and developed a reputation for maintaining the strictest privacy in all her interactions. Still wary of strangers, she slowly began to trust others, and started to feel more safe. Limiting her self-disclosure, she opened up enough to maintain her new relationships, just a crack.

Men were a problem. She had never had a serious relationship with a man, and her cultural background led her to believe that she was irreparably damaged by what she regarded as “her shame.” Her female friends were largely single, and wanted to talk about dating. Zizi listened, but kept her personal window all but shut. Like Victoria and Mikage, two women she would soon meet, she had good reasons to believe men were pigs. But it really didn’t matter whether or not men were good or bad. She remained fixed on nothing but survival--no room for much else.

In the cafeteria one day, Charlene, a new friend, suggested she get out more.

“There’s a benefit supper on Friday night up near Pellston.”

“To benefit what?”

“There’s a man who needs a new kidney...has no health benefits.”

“How can people not have health benefits in America?”

“Way it is...you want to go with?”

“Do I need to wear something?”

“Yes, you should wear clothes, silly.”

“Is it safe up there?”

“Stick with me...I’ll keep you safe.”

“Okay...but it’s no place for me if there are bears around?”

“No bears...promise.”

“Where is it again?”

“Across from Moose Jaw Junction.”

“Moose, jaws, a junction for mooses?”

“No moose...it’s a bar.”

“Okay.”

Charlene picked Zizi up outside her apartment on Friday evening, and drove north towards Pellston. In the dimming sky, three deer abruptly crossed in front of the car, confirming Zizi’s sense of danger, never entirely absent. Walking into the meeting hall from the parking lot, Zizi looked over her shoulder, keeping a sharp look-out for wild animals. Unaware of the real danger waiting inside the hall, she was about to be captured by Nick Randall, a man that she would find difficult to out talk, out walk, or out run.

No comments:

Post a Comment